Make a point of visiting us weekly!

Return to Becoming a Learner CONTENTS PAGE

Page 12: The Learning Process - Getting it (Understanding)

In the previous pages on Memory, we commented in the list of things that help memory work, that understanding helps memory. Let’s now go further and say in the learning process, if you don’t understand you don’t learn.

Part 2: The Adventure of Learning

All we hope to do here on this page is give you a little insight into what is going in and what is involved in your learning process. Awareness of what is taking place helps. The more you can see this, the more you will want to develop your learning skills.

What has always amazed me, when I’ve thought about it, is that with virtually all exam boards you can still pass with a relatively low mark. Suppose you pass with a mark of 60%. That means you fell short of answering the questions by 40%. You didn’t know two fifths of the work!

What has always amazed me, when I’ve thought about it, is that with virtually all exam boards you can still pass with a relatively low mark. Suppose you pass with a mark of 60%. That means you fell short of answering the questions by 40%. You didn’t know two fifths of the work!

The Importance of Understanding

Well perhaps it isn’t as simple as that but, for whatever reason, a lot of us don’t reach the expectations of the examiners and leave large gaps in our understanding. If knowledge is all about collecting the right facts together for our subject, understanding is seeing the significance of those facts.

Well perhaps it isn’t as simple as that but, for whatever reason, a lot of us don’t reach the expectations of the examiners and leave large gaps in our understanding. If knowledge is all about collecting the right facts together for our subject, understanding is seeing the significance of those facts.

By way of example, let’s very briefly consider William Wordsworth’s Poem, “I wandered lonely as a Cloud” otherwise known as “The Daffodils”. Now if we were studying that poem, we would almost certainly first read it and familiarise ourselves with it. We have the basic facts (knowledge) of what the poem says.

But then we might research a little further and find that “It was inspired by an April 15, 1802 event in which Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy walked around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District, and came across a ‘long belt’ of daffodils.” (Wikipedia)

But then we might research a little further and find that “It was inspired by an April 15, 1802 event in which Wordsworth and his sister, Dorothy walked around Glencoyne Bay, Ullswater, in the Lake District, and came across a ‘long belt’ of daffodils.” (Wikipedia)

A little more research and we find, “the memory of the daffodils is etched in the speaker's mind and soul to be cherished forever. When he's feeling lonely, dull or depressed, he thinks of the daffodils and cheers up. The full impact of the daffodils' beauty (symbolizing the beauty of nature) did not strike him at the moment of seeing them, when he stared blankly at them but much later when he sat alone, sad and lonely and remembered them”

Further reading reveals the reception the poem received and what others thought about it. A final phase might be for any reader (yourself) to then record the impact the poem has had on you.

From this very simple illustration we see that “understanding” takes us from the basic facts of ‘what’ to ‘where and when’ and then ‘why’ and then beyond that to its impact or significance on the lives of other people.

This assessment of ‘understanding’ as we have just put it, can be applied to virtually anything, but of course in some subjects going beyond ‘what’ is simply an understanding of why something is as it is. To take the most simple of examples in maths, a teacher might state, “The area of a right angle triangle is half the base times the height.” Basic facts! To go on an explain why that simple formula is true would be to bring understanding.

Further reading reveals the reception the poem received and what others thought about it. A final phase might be for any reader (yourself) to then record the impact the poem has had on you.

From this very simple illustration we see that “understanding” takes us from the basic facts of ‘what’ to ‘where and when’ and then ‘why’ and then beyond that to its impact or significance on the lives of other people.

This assessment of ‘understanding’ as we have just put it, can be applied to virtually anything, but of course in some subjects going beyond ‘what’ is simply an understanding of why something is as it is. To take the most simple of examples in maths, a teacher might state, “The area of a right angle triangle is half the base times the height.” Basic facts! To go on an explain why that simple formula is true would be to bring understanding.

In physics it may appear to be more complicated, but that will only be so if you are not familiar with it. Matter, we are told exists in one of three states – liquid, gas or solid – and each of these can be broken down into component parts, the elements. So here we have water which can be divided into molecules which in turn can be further taken down into atoms of the elements hydrogen and oxygen. Within each atom there are subatomic particles – protons, neutrons and electrons and the former two are composed of even tinier particles called quarks. Understanding how these all work together and with other materials may possibly be called just collecting facts together or you may speak of understanding how they interact etc.

Perhaps we are trying to be too clever here. However, the point we are trying to make is that in the learning process we start by collecting facts together and then we try to give some significance to those facts and that significance we call understanding.

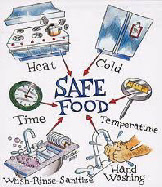

To use a completely different example, in the matter of food hygiene, on a course about keeping food safely, we might find the following instructions:

-

It is only when you look into the ‘why’ of these instructions that you will understand the significance of them. (You can look it up on the Internet.) Understanding takes us beyond basic facts.

One more example before we move on. In the sky we so often see clouds. There are Cumulus or heaped clouds, Cirrus or feathery, curly, hair-like clouds, or Stratus or layered clouds at lower levels that we get on overcast days. There you are, basic facts or descriptions.

The Learner then asks, “Why are they like that? Is it that simple?” and suddenly whole big areas of future learning are opened up.

The Learner then asks, “Why are they like that? Is it that simple?” and suddenly whole big areas of future learning are opened up.

Don’t be awe-struck

Not all of us are Einstein’s and therefore our “what, where, when, why” questions may only take us on a few stages, but don’t despise even that. If you really want the other extreme, you will find writings around that defy most people. Stephen Hawking’s book, “A Brief History of Time” is said to have sold over ten million copies.

Talking to one bright person who ploughed their way through it, they said to me, “I doubt if I understood a tenth of it,” so don’t be put off if super bright people write things beyond most of us. Their problem is that there are few around who can challenge what they write, especially when the writing verges on philosophical speculation.

Not all of us are Einstein’s and therefore our “what, where, when, why” questions may only take us on a few stages, but don’t despise even that. If you really want the other extreme, you will find writings around that defy most people. Stephen Hawking’s book, “A Brief History of Time” is said to have sold over ten million copies.

Talking to one bright person who ploughed their way through it, they said to me, “I doubt if I understood a tenth of it,” so don’t be put off if super bright people write things beyond most of us. Their problem is that there are few around who can challenge what they write, especially when the writing verges on philosophical speculation.

A word to the wise here. Do not be awe-struck by authors. Having been a college lecturer for a number of years I can come up with a number of anecdotes but will limit myself to one. A colleague of mine had a respectable text book and coming across some research figures rang the author up, who he knew, asking for some more details. The author confessed to him, “Oh I just made up those figures. I knew that that’s roughly what they ought to be.”

If you really want an interesting study, research the number of scientific scams that there have been in the last hundred years. The lack of intellectual integrity was of sufficient concern a few years ago that it made it into the popular media. This is not to despise all you read, but remain a questioner.

A seeker of understanding continues to ask the questions – what, where, when why, how?

This page is continued on Page 12A

If you really want an interesting study, research the number of scientific scams that there have been in the last hundred years. The lack of intellectual integrity was of sufficient concern a few years ago that it made it into the popular media. This is not to despise all you read, but remain a questioner.

A seeker of understanding continues to ask the questions – what, where, when why, how?

This page is continued on Page 12A